Python tools for random data analysis.

This module (random_data) aims to provide Python tools for

flexible and extensible analysis of random signals

(see example use cases below).

The motivation and mathematical underpinnings of this module

are largely discussed in Bendat and Piersol's classic text "Random Data", and

inquisitive users are directed there for a thorough discussion

of the methodologies implemented in this module.

The matplotlib.mlab submodule offers several useful routines

for spectral density estimation, but

-

psdandcsd, which use Welch's average periodogram method to estimate the autospectral density and cross-spectral density, respectively, are not time-resolved, and -

specgram, which creates a time-resolved estimate of the autospectral density (i.e. a "spectrogram"), does not average spectral estimates over several realizations, so the resulting spectrogram suffers from large amounts of random error

In contrast, random_data produces time-resolved spectral density estimates

that have been averaged over several realizations, effectively merging

the functionality of psd/csd and specgram. This is largely accomplished

via class definitions built around matplotlib's psd and csd functions.

In addition, random_data provides:

- a class to fit the cross-phase angles from an array of measurements to a linear model, allowing determination of mode numbers/wavenumbers as a function of frequency and time,

- a class to estimate the complex-valued, spatial cross-correlation function from an array of measurements (the array need not be uniformly spaced),

- a class to estimate the two-dimensional autospectral density from an array of measurements (the array need not be uniformly spaced),

- robust methods for visualizing the relevant spectral estimates (magnitude, coherence, phase angle, mode number, and quality of fit),

- a class for autoregressive (AR) autospectral-density estimation,

- a class for "spike" identification and removal from spectral estimates, and

- a class for determining the "trigger offset" between a collection of time series.

The installation and use of random_data are discussed below.

Package management is cleanly handled on Iris via

modules.

The random_data package has a corresponding modulefile

here.

To use the random_data package, change to the directory

you'd like to download the source files to and

retrieve the source files from github by typing

$ git clone https://github.com/emd/random_data.git

The created random_data directory defines the

package's top-level directory.

The modulefiles should be similarly cloned.

Now, at the top of the corresponding

modulefile,

there is a TCL variable named random_data_root;

this must be altered to point at the

top-level directory of the cloned random_data package.

That's it! You shouldn't need to change anything else in

the modulefile. The random_data module can

then be loaded, unloaded, etc., as is discussed in the

above-linked Iris documentation.

The modulefile also defines a series of automated tests

for the random_data package. Run these tests at the command line

by typing

$ test_random_data

If the tests return "OK", the installation should be working.

Change to the directory you'd like to download the source files to and retrieve the source files from github by typing

$ git clone https://github.com/emd/random_data.git

Change into the random_data top-level directory by typing

$ cd random_data

For accounts with root access, install by running

$ python setup.py install

For accounts without root access (e.g. a standard account on GA's Venus cluster), install locally by running

$ python setup.py install --user

To test your installation, run

$ nosetests tests/

If the tests return "OK", the installation should be working.

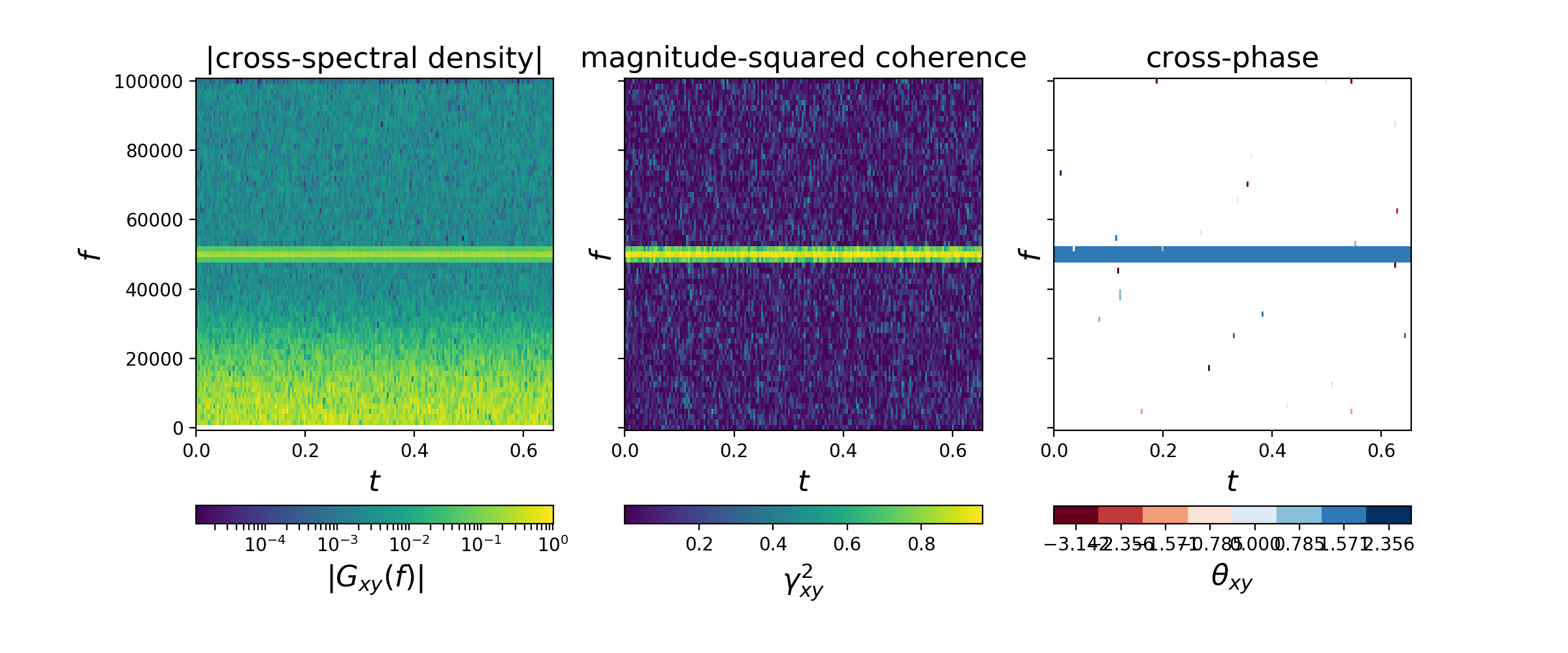

random_data allows easy computation and visualization

of various spectral quantities (e.g. spectral densities,

coherence, cross-phase). For example, the below code

spectrally analyzes two "measurements" of a 50 kHz signal

in the presence of non-white noise and plots:

- the magnitude of the cross-spectral density as a function of frequency vs. time (left),

- the magnitude-squared coherence as a function of frequency vs. time (middle), and

- the cross-phase angle as a function of frequency vs. time (right).

(Note that most of the code below is to generate representative fake signals, while the spectral computations only involve initialization of a single object.)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random_data as rd

# =============================================================================

# Generate some fake data:

# ------------------------

# Parameters of digitized record

Fs = 200e3 # sample rate, [Fs] = samples / s

t0 = 0 # initial time, [t0] = s

T = 1 # (approximate) record length, [T] = s

# Generate two random signals

tau = 4. / Fs # correlation time

sig1 = rd.signals.RandomSignal(Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T, tau=tau)

sig2 = rd.signals.RandomSignal(Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T, tau=tau)

# Add a coherent signal with well-known phase difference

A = 20. # amplitude, [A] = [sig1.x]

f0 = 50e3 # frequency, [f0] = Hz

theta12 = np.pi / 2 # cross-phase, [theta12] = radian

omega0_t = 2 * np.pi * f0 * sig1.t()

sig1.x += (A * np.cos(omega0_t))

sig2.x += (A * np.cos(omega0_t + theta12))

# =============================================================================

# =============================================================================

# Perform spectral analysis:

# --------------------------

# Spectral-estimation parameters

Tens = 5e-3 # ensemble time, [Tens] = s

Nreal_per_ens = 10 # number of realizations per ensemble

csd = rd.spectra.CrossSpectralDensity(

sig1.x, sig2.x, Fs=sig1.Fs, t0=sig1.t0,

Tens=Tens, Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

# Create plots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, sharex=True, sharey=True, figsize=(12, 5))

csd.plotSpectralDensity(ax=axes[0], title='|cross-spectral density|')

csd.plotCoherence(ax=axes[1], title='magnitude-squared coherence')

csd.plotPhaseAngle(ax=axes[2], title='cross-phase')

plt.show()

# =============================================================================Note that the cross-phase angle (pi / 2) is correctly identified in the above spectral calculations. Further, note that the cross-phase is only plotted for points with magnitude-squared coherence exceeding a user-specified threshold.

If only one signal is available for analysis,

the random_data.spectra.AutoSpectralDensity class

is available for computing autospectral densities.

(Of course, by definition, the coherence is unity and

the phase angle zero for all frequencies and times

in the autospectral density).

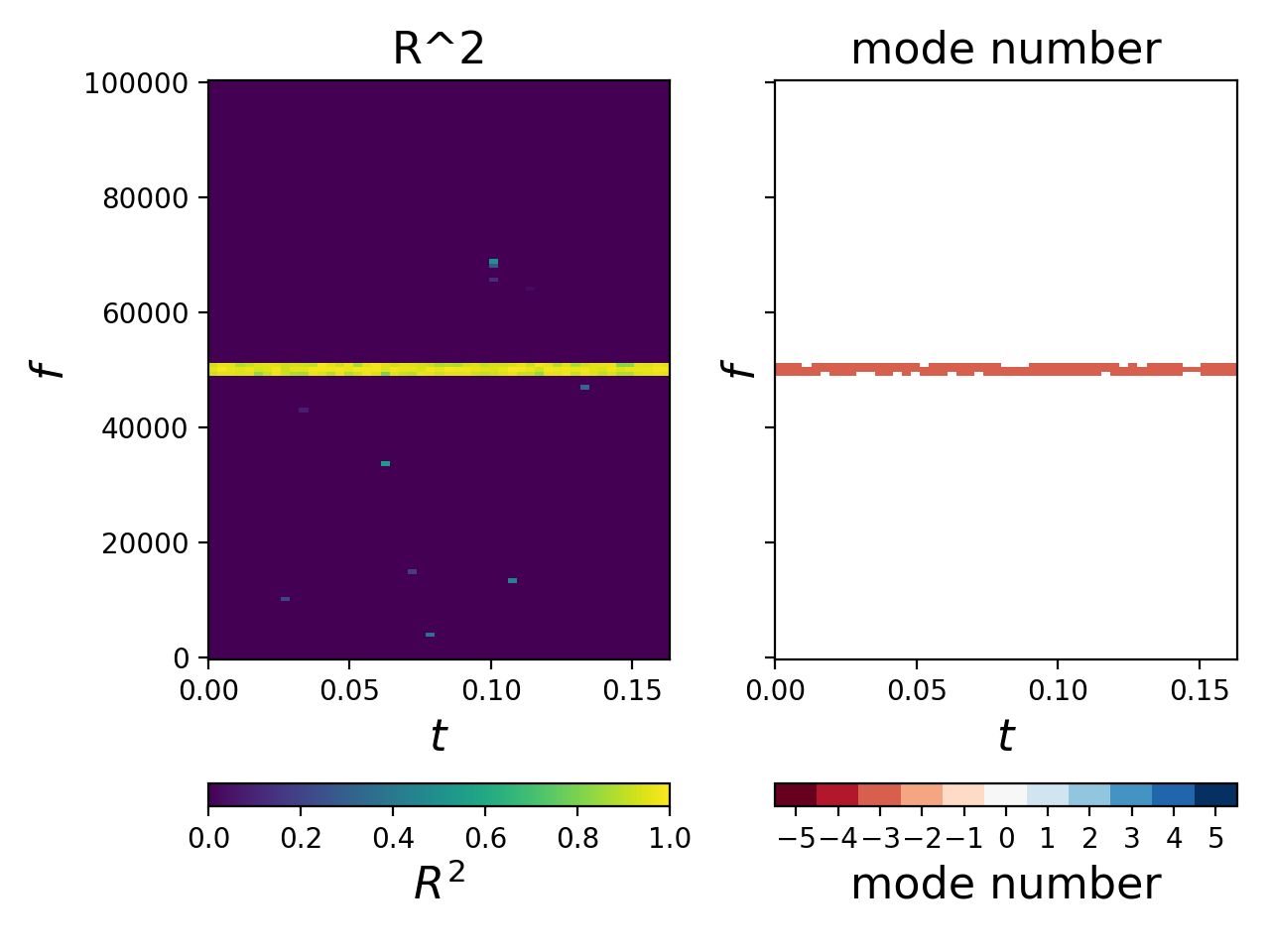

If more than two measurements are available, noise in mode-number

calculations can be greatly reduced by fitting the cross-phase angles

of each individual measurement pair to a linear model.

The random_data.array.FittedCrossPhaseArray class allows for

easy fitting and visualization of cross-phase angles

to obtain the corresponding mode numbers.

For example, the below code

spectrally analyzes an array of measurements of a 50 kHz signal

in the presence of non-white noise and plots:

- the coefficient of determination, R^2 (i.e. quality of fit, with larger R^2 being indicative of a better fit), as a function of frequency vs. time (left), and

- the mode number as a function of frequency vs. time (right).

(Note that most of the code below is to generate representative

fake signals, while the spectral computations only involve

initialization of a single object.

For analysis of DIII-D magnetics signals, for example,

a simple package exists

for fetching and organizing the magnetics data in a format

that is readily compatible with random_data.array.FittedCrossPhaseArray.)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random_data as rd

# =============================================================================

# Generate some fake data:

# ------------------------

# Parameters of digitized record

Fs = 200e3 # sample rate, [Fs] = samples / s

t0 = 0 # initial time, [t0] = s

T = 0.2 # (approximate) record length, [T] = s

# Measurement locations

locations = (np.pi / 180) * np.array(

[67.5, 97.4, 127.8, 137.4, 157.6, 246.4, 277.5, 307, 312.4, 317.4, 339.8])

Nsig = len(locations)

# Generate representative random signal

tau = 8. / Fs

sig = rd.signals.RandomSignal(Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T, tau=tau)

Npts = len(sig.t())

# Initialize signal array

signals = np.zeros((Nsig, Npts))

# Coherent signal properties

A0 = 25. # amplitude, [A0] = [sig1.x]

f0 = 50e3 # frequency, [f0] = Hz

n = -3 # mode number

omega0_t = 2 * np.pi * f0 * sig.t()

# Loop through measurement locations, creating corresponding

# coherent signal corrupted by noise at each point

for i in np.arange(Nsig):

# Phase shift from mode number

dtheta = n * (locations[i] - locations[0])

# Coherent signal with mode-number dependence

signals[i, :] = A0 * np.cos(omega0_t + dtheta)

# Uncorrelated noise

signals[i, :] += (rd.signals.RandomSignal(Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T, tau=tau)).x

# =============================================================================

# =============================================================================

# Perform spectral analysis:

# --------------------------

# Spectral-estimation parameters

Tens = 5e-3 # ensemble time, [Tens] = s

Nreal_per_ens = 4 # number of realizations per ensemble

A = rd.array.FittedCrossPhaseArray(

signals, locations, Fs=sig.Fs, t0=sig.t0,

Tens=Tens, Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

# Create plots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharex=True, sharey=True)

A.plotR2(ax=axes[0], title='R^2')

A.plotModeNumber(ax=axes[1], title='mode number')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# =============================================================================Note that the mode number (n = -3) is correctly identified in the above computations. Further, note that the mode number is only plotted for points with R^2 exceeding a user-specified threshold that can be specified on the fly.

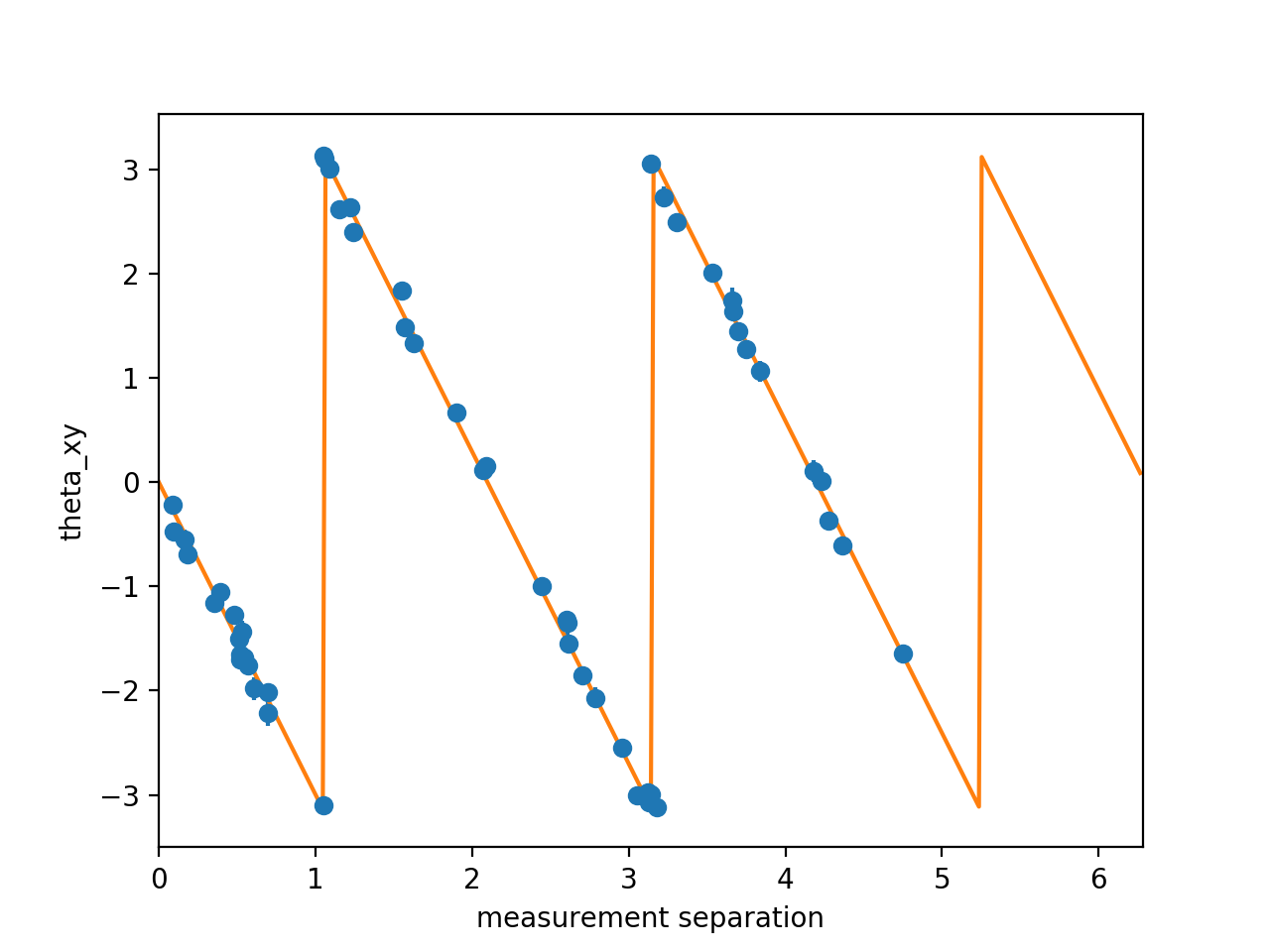

Further, to easily examine the fit at a given frequency and time (say 50 kHz and 0.05 s), simply use:

# Using the object `A` created from running the above code

A.plotSlice('theta_xy', f=50e3, t=0.05)The error bars (barely visible)

indicate the random error in the estimated cross-phase angle.

Plotting slices of other spectral quantities

('Gxy' for cross-spectral density,

'gamma2xy' for magnitude-squared coherence)

can be similarly created by substituting the appropriate string

in place of 'theta_xy'.

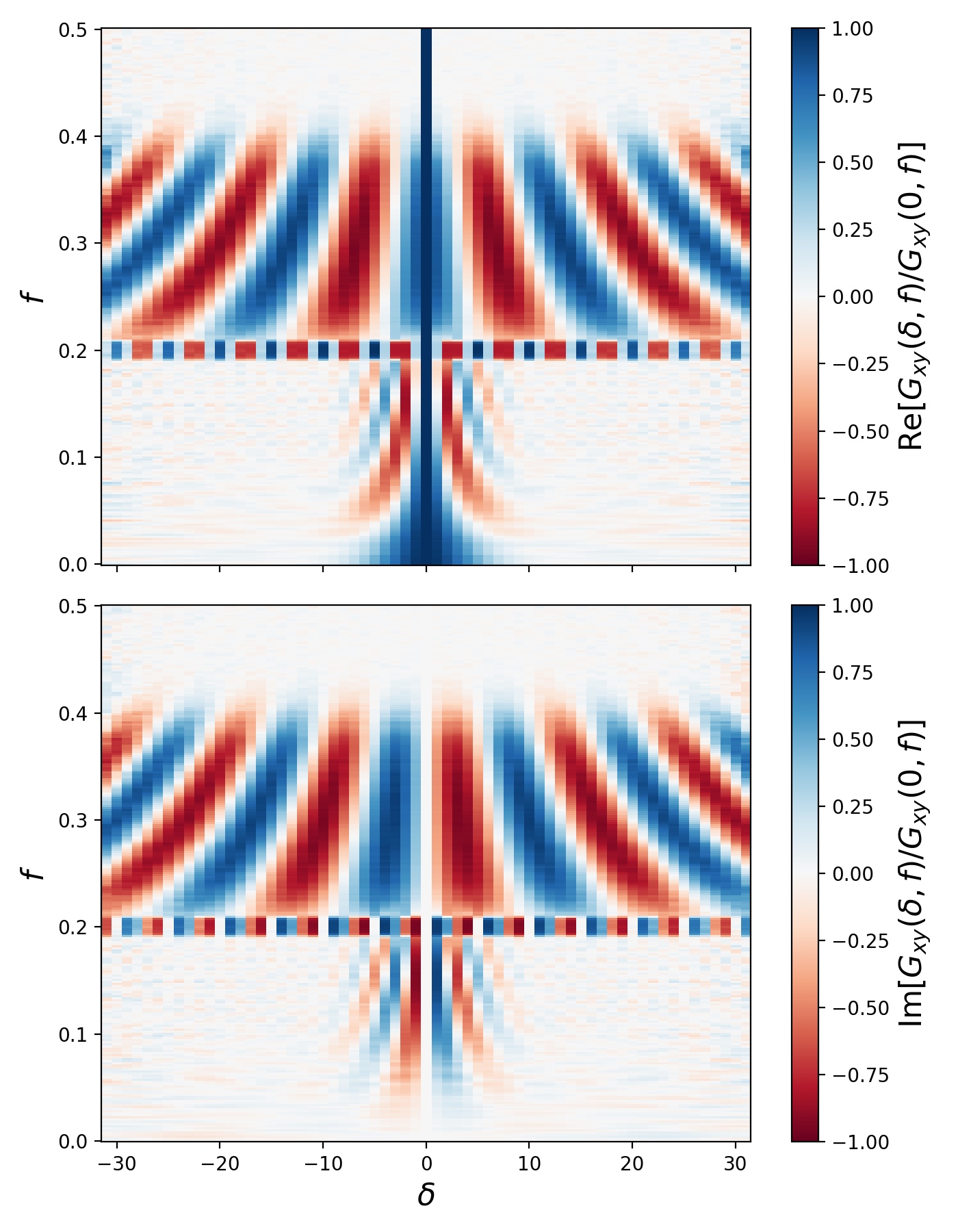

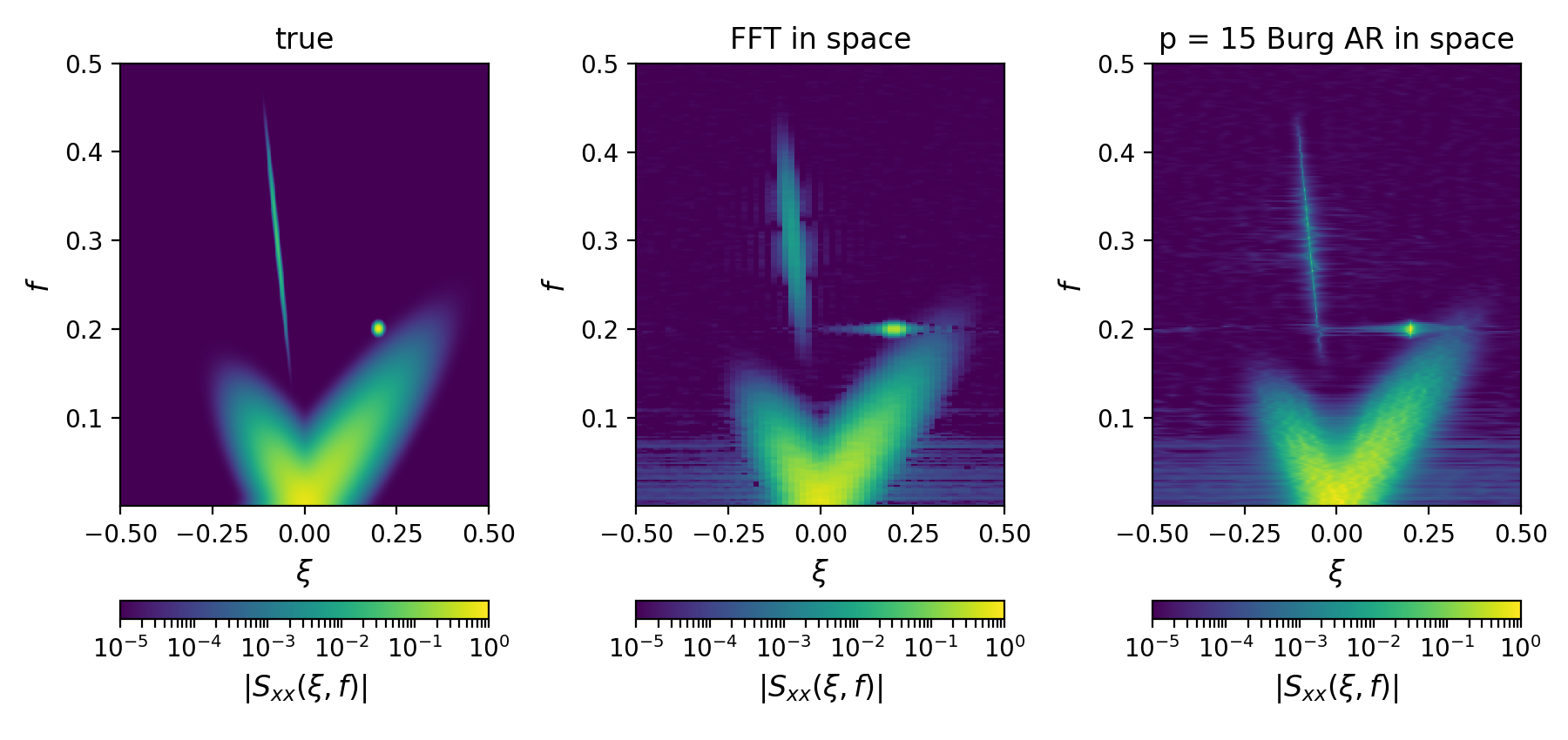

If more than two measurements are available and there is a broadband spatial

component, a two-dimensional autospectral density S(xi, f), where

xi is the spatial frequency and f is the temporal frequency,

can be much more informative that the mode-number spectra above.

The random_data.spectra2d.TwoDimensionalAutoSpectralDensity class

allows for easy computation and visualization of S(xi, f);

the random_data.spectra2d.TwoDimensionalAutoSpectralDensity class

takes a complex-valued, spatial cross-correlation function as input, which

can similarly be easily computed and visualized via the

random_data.array.SpatialCrossCorrelation class.

For example, the below code computes the two-dimensional complex-valued

correlation function and the two-dimensional autospectral density of

a model signal with multiple fluctuation branches.

(Note that most of the code below is to generate a model signal

with multiple fluctuation branches,

while the spectral computations only involve

initialization of two objects,

one for the correlation function and

one for the two-dimensional autospectral density.

For analysis of DIII-D PCI signals, for example,

a package exists

for fetching and organizing the PCI data in a format

that is readily compatible with random_data.array.SpatialCrossCorrelation.)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random_data as rd

# =============================================================================

# Signal parameters:

# ------------------

# Spatial-grid parameters

Fs_spatial = 1 # spatial sample rate, [Fs_spatial] = samples / [distance]

z0 = 0 # initial spatial sample, [z0] = 1 / [Fs_spatial]

Z = 512

# Temporal-grid parameters

Fs = 1. # sample rate, [Fs] = samples / s

t0 = 0 # initial time, [t0] = s

T = 32768 # (approximate) temporal record length, [T] = s

# Parameters of each fluctuation branch

# (Here, we specify 4 distinct branches, each with unique characteristics)

xi0 = [0.0, 0., -0.075, 0.2]

Lz = [ 2.5, 4., 25., 50.]

f0 = [ 0., 0., 0., 0.2]

tau = [10., 10., 25., 100.]

v = [ 0.5, -0.5, -4., 0.]

S0 = [ 1., 1., 0.1, 3.]

# Noise-floor parameters

noise_floor = 1e-5

seed = None

# Create signal object:

# ---------------------

sig = rd.signals.RandomSignal2d(

Fs_spatial=Fs_spatial, z0=z0, Z=Z,

Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T,

xi0=xi0, Lz=Lz, f0=f0, tau=tau, v=v, S0=S0,

noise_floor=noise_floor, seed=seed)

# Sample only a subset of spatial locations:

# ------------------------------------------

# Why? The answer is twofold:

#

# (1) The broadband signal is constructed via the inverse FFT, which

# implicitly imposes periodicity in the spatial and temporal domains.

# This produces a complex-valued, spatial cross-correlation function

# that has large correlations at large spatial separations, which

# is not typically seen in actual experimental data. Restricting

# the spatial sampling to *at most* one half of the spatial domain

# prevents these "unphysical" correlations.

#

# (2) In practice, sampling in time is "cheap" while sampling in space

# is "expensive" (i.e. additional channels can require large upfront

# capital investment). Thus, in practice, the number of channels

# is often limited. Above, we created a broadband signal with a

# high degree of spectral resolution, but we may not have the

# required number of channels to reconstruct the spectrum at

# the full resolution.

#

# The spatial sampling can be easily altered by changing the parameter

# `spatial_sampling` below.

spatial_sampling = slice(None, 32)

x = sig.x[spatial_sampling, :]

z = sig.z()[spatial_sampling]

# =============================================================================

# =============================================================================

# Complex-valued, spatial cross-correlation function:

# ---------------------------------------------------

Nreal_per_ens = 100 # number of realizations per ensemble

corr = rd.array.SpatialCrossCorrelation(

x, z, Fs=Fs, t0=t0,

Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

corr.plotNormalizedCorrelationFunction()

plt.show()

# Two-dimensional autospectral density:

# -------------------------------------

# ... via Fourier method

asd2d_fourier = rd.spectra2d.TwoDimensionalAutoSpectralDensity(

corr, spatial_method='fourier',

fourier_params={'window': np.hanning})

# ... via Burg method

p = 15 # AR order for Burg estimate

Nxi = 1000 # Number of points in spatial grid for Burg estimate

asd2d_burg = rd.spectra2d.TwoDimensionalAutoSpectralDensity(

corr, spatial_method='burg',

burg_params={'p': p, 'Nxi': Nxi})

# Compare true autospectral density to Fourier and Burg methods:

# --------------------------------------------------------------

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(9, 4.25))

fontsize = 12

vlim = [sig._noise_floor, np.max(sig._Sxx)]

sig.plotSpectralDensity(

ax=axs[0],

title='true',

fontsize=fontsize,

vlim=vlim)

asd2d_fourier.plotSpectralDensity(

ax=axs[1],

title='FFT in space',

fontsize=fontsize,

vlim=vlim)

asd2d_burg.plotSpectralDensity(

ax=axs[2],

title='p = %i Burg AR in space' % p,

fontsize=fontsize,

vlim=vlim)

plt.tight_layout()

# Tight layout alters tick labels...

for ax in axs:

ax.set_xticks([-0.5, -0.25, 0, 0.25, 0.5])

ax.set_yticks([0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5])

plt.show()

# # Compare Fourier and Burg methods

# vlim = [noise_floor, np.max(sig._Sxx)]

# fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharex=True, sharey=True, figsize=(12, 5))

# asd2d_fourier.plotSpectralDensity(ax=axes[0], title='Fourier', vlim=vlim)

# asd2d_burg.plotSpectralDensity(ax=axes[1], title='Burg', vlim=vlim)

# plt.show()

# =============================================================================Here, contributions from both the broadband and coherent signals are visible.

Note that this is a plot of the normalized complex-valued, spatial

cross-correlation function. That is, at each frequency f,

the correlation function Gxy(delta, f) is normalized to Gxy(0, f)

(i.e. its value at zero separation (delta = 0) and frequency f).

This allows for easy visualization of the correlation function's structure

even if Gxy(delta, f) varies by several orders of magnitude as

the frequency varies.

Here, in the two-dimensional autospectral density estimates,

the contributions from both the broadband and coherent signals

are clearly visible.

Note that f is the temporal frequency and

that xi is the spatial frequency

(related to the usual wavenumber k via k = 2 * np.pi * xi).

Further, note that the spatial spectral estimates

can be estimated from the correlation function corr via

a 'fourier' or 'burg' method.

The Burg method can produce superior resolution

particularly when the number of spatial samples are limited, but

the Burg method is also subject to "pole splitting", which

typically becomes more manifest as the pole order p is increased.

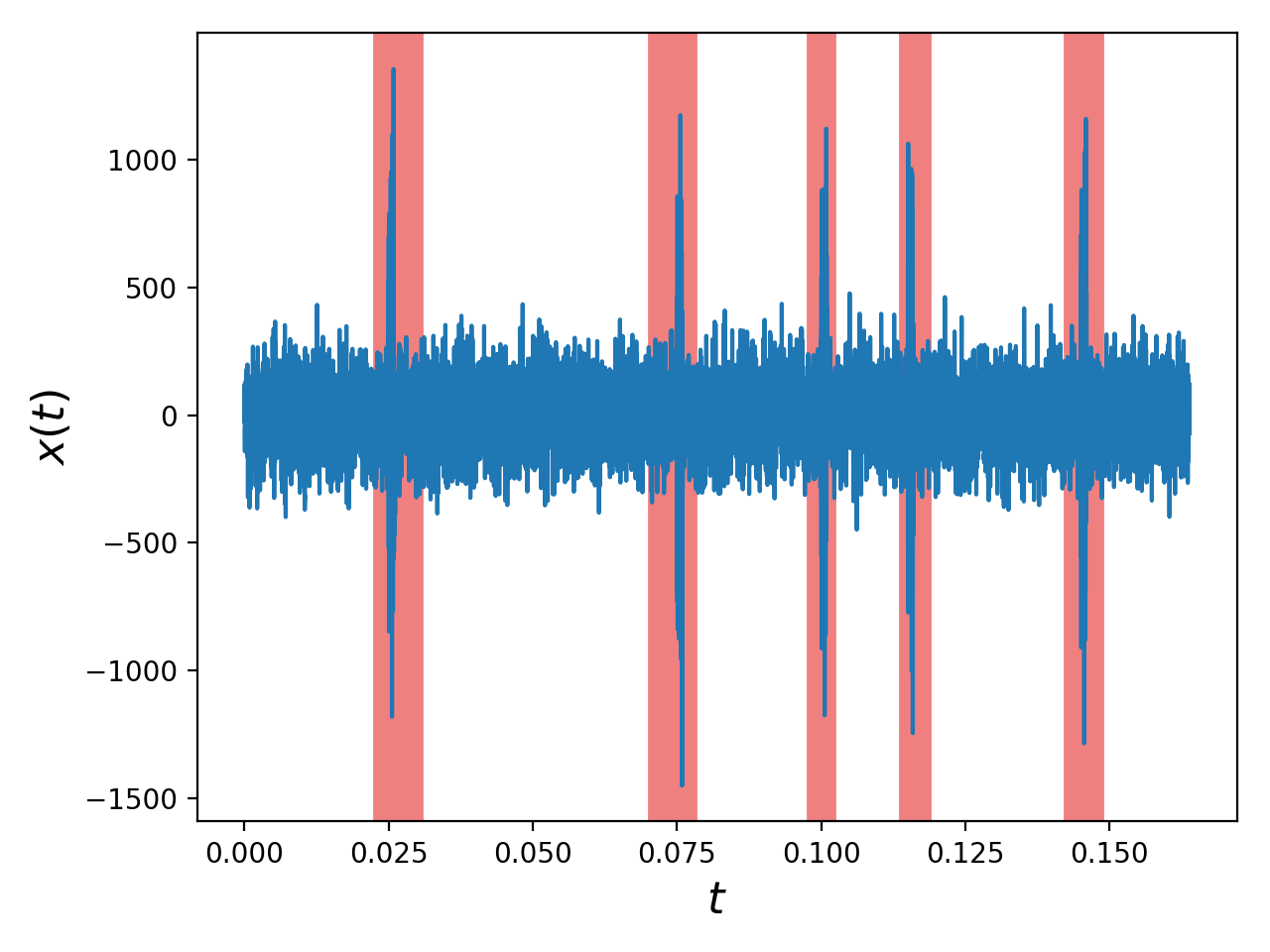

Spikes, whether physical or an artifact of a given measurement,

may find their way into a random signal.

Such spikes must be removed from the signal

prior to performing spectral calculations

to prevent corruption of the spectral estimates.

The random_data.signals.SpikeHandler class allows for

robust identification and visualization of spikes and

easy removal of spike-induced contributions

to the spectral estimates.

(Note that most of the code below is to generate representative fake signals, while spike identification only requires initialization of a single object and spike visualization only requires the subsequent evaluation of a single method.)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random_data as rd

# =============================================================================

# Generate some fake data:

# ------------------------

# Parameters of digitized record

Fs = 200e3 # sample rate, [Fs] = samples / s

t0 = 0 # initial time, [t0] = s

T = 0.2 # (approximate) record length, [T] = s

# Generate representative random signal

f0 = 0.

tau = 4. / Fs

G0 = 1.

noise_floor=1e-5

seed = None

sig = rd.signals.RandomSignal(

Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T,

f0=f0, tau=tau, G0=G0,

noise_floor=noise_floor, seed=seed)

# Add "spikes" to various points of signal

N = 200

spike = 3 * np.std(sig.x) * np.random.randn(N)

sig.x[5000:(5000 + N)] += spike

sig.x[15000:(15000 + N)] -= spike

sig.x[20000:(20000 + N)] += spike

sig.x[23000:(23000 + N)] -= spike

sig.x[29000:(29000 + N)] += spike

# =============================================================================

# =============================================================================

# Detect spikes:

# --------------

sigma_mult = 5 # detect spikes that at 5x the RMS of `sig.x`

debounce_dt = 5e-3 # distinct spikes must be at least 5 ms apart

SH = rd.signals.SpikeHandler(

sig.x, Fs=sig.Fs, t0=sig.t0,

sigma_mult=sigma_mult, debounce_dt=debounce_dt)

# Plot original signal, highlighting spikes:

# ------------------------------------------

window_fraction = [0.1, 0.9]

SH.plotTraceWithSpikeColor(sig.x, sig.t(), window_fraction=window_fraction)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

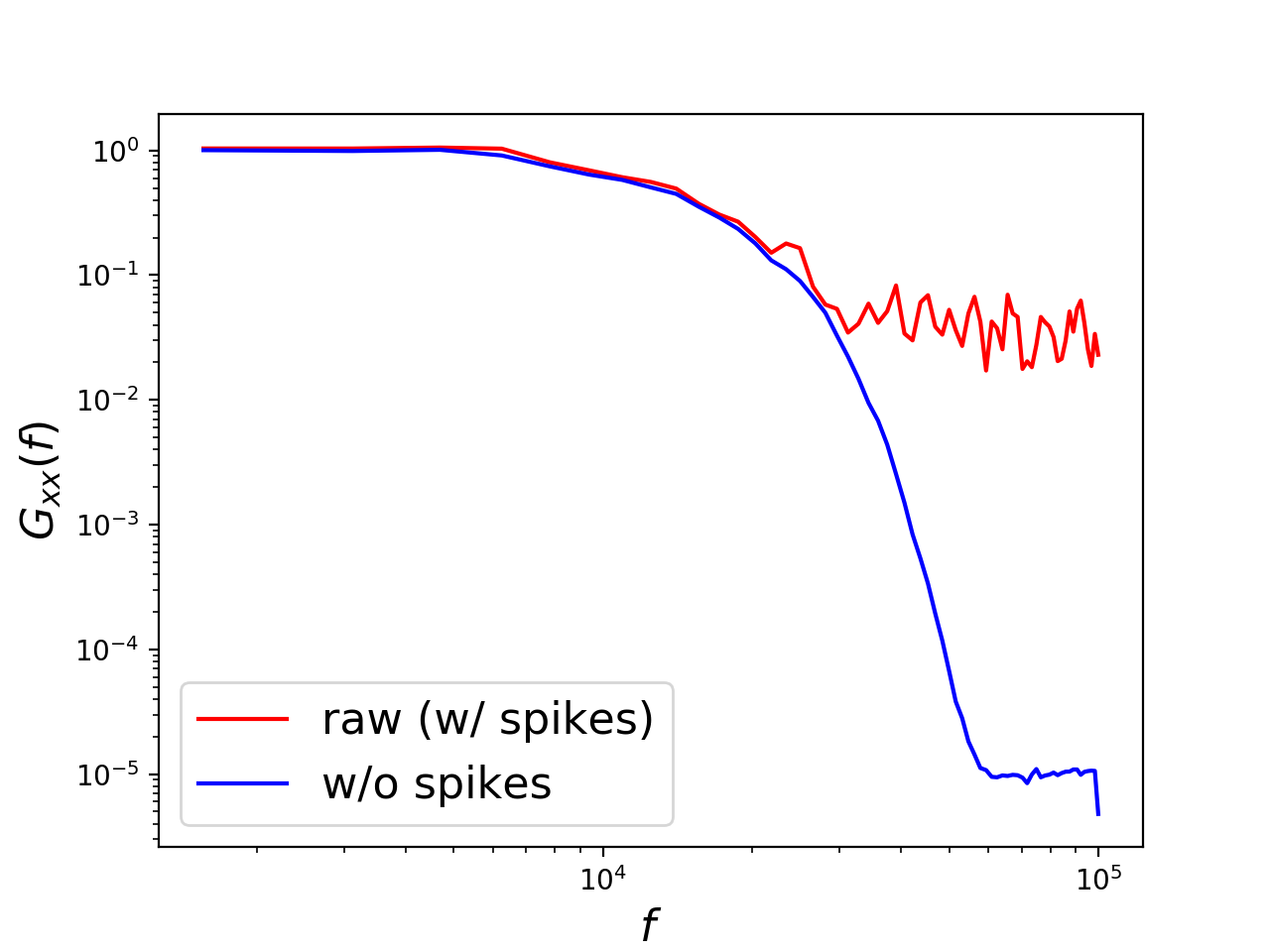

# =============================================================================The effects of including vs. excluding the spikes from the spectral computations can be easily evaluated:

# Spectral calculations:

# ----------------------

# Spectral-estimation parameters

Tens = 1e-3 # ensemble time, [Tens] = s; *LESS* than spike spacing!!!

Nreal_per_ens = 1 # will perform averaging later, after spike removal

asd = rd.spectra.AutoSpectralDensity(

sig.x, Fs=sig.Fs, t0=sig.t0,

Tens=Tens, Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

# Average over all contributions, including spikes

Gxx_raw = np.mean(asd.Gxx, axis=-1)

# Average only over `window_fraction` of spike-free windows

ind = SH.getSpikeFreeTimeIndices(asd.t, window_fraction=window_fraction)

Gxx_no_spikes = np.mean(asd.Gxx[:, ind], axis=-1)

# Plot difference between raw and spike-free spectra:

# ---------------------------------------------------

fontsize = 16

plt.figure()

plt.loglog(asd.f, Gxx_raw, 'r')

plt.loglog(asd.f, Gxx_no_spikes, 'b')

plt.xlabel(r'$f$', fontsize=fontsize)

plt.ylabel(r'$G_{xx}(f)$', fontsize=fontsize)

plt.legend(['raw (w/ spikes)', 'w/o spikes'],

loc='lower left', fontsize=fontsize)

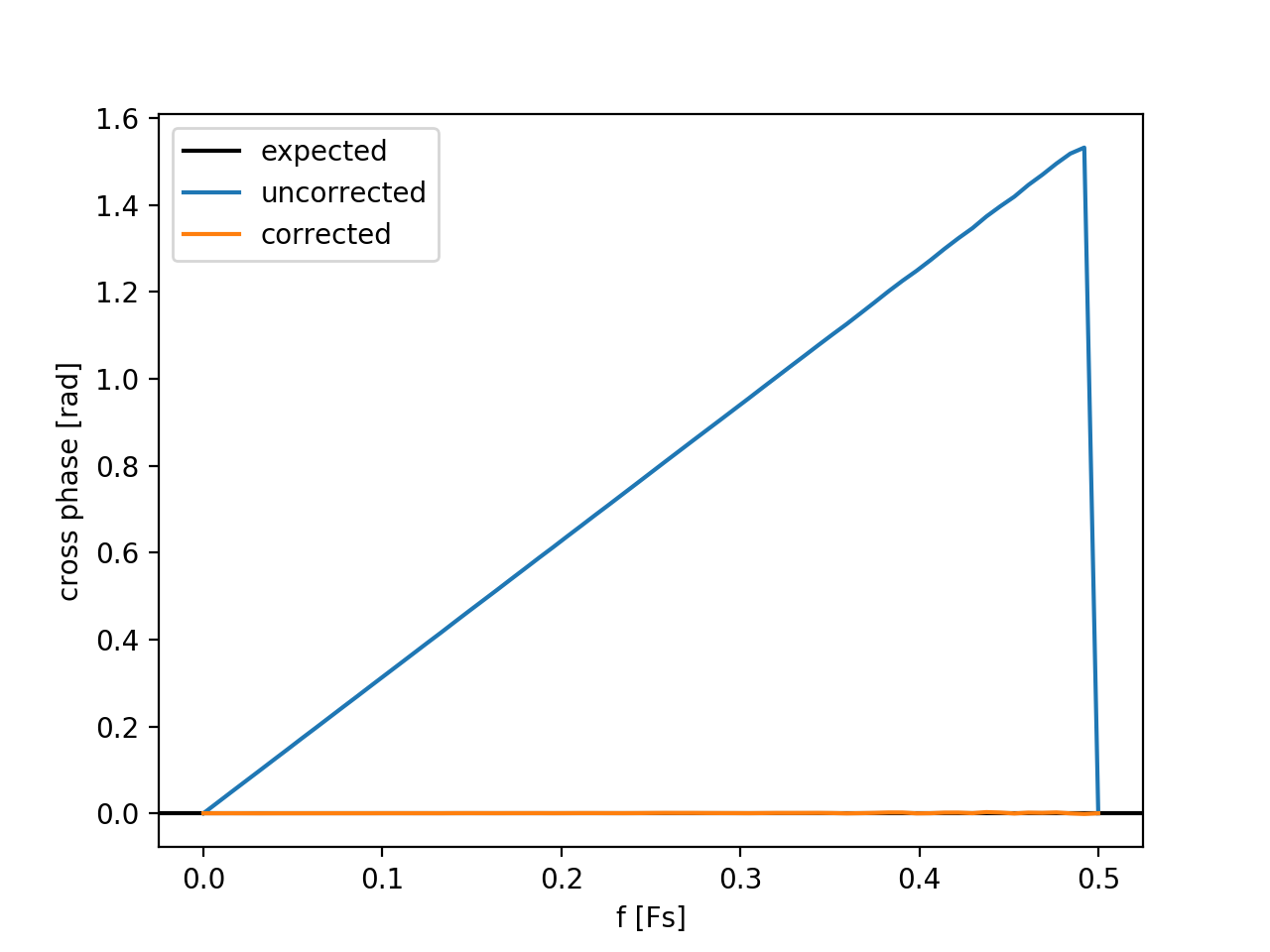

plt.show()Accurately estimating spectral quantities of a given random process

from a collection of digital records requires (among other things)

that the true, physical timebase of the process is well-represented

by the nominal timebase of the digital record. If two records x1

and x2 have the same nominal time base but, for example,

digitization of record x2 actually begins a finite time tau later

than the digitization of record x1, then naively computed spectral

estimates will be biased away from their true, physical values.

The random_data.signals.TriggerOffset class allows for

easy estimation of such trigger offsets, as demonstrated below.

(Note that most of the code below is required

to generate representative fake signals and

to visualize the data, while

estimating the trigger only requires initialization of a single object;

subsequent compensation of the trigger offset

only requires calling a single function).

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import random_data as rd

# =============================================================================

# Generate some fake data:

# ------------------------

# Nominal temporal-grid parameters

Fs = 1. # sample rate, [Fs] = arbitrary units

t0 = 0 # nominal trigger time, [t0] = s

T = 1e5 # (approximate) record length, [T] = s

# Discrepancy `tau` between timebase of digital record 1 and

# timebase of digital record 2. Note that, as defined here,

# `tau` is *not* an integer of the sample spacing; that is,

# the trigger-offset estimation and compensation works for

# arbitrary `tau`.

tau = 0.5 / Fs # [tau] = s, nonzero

# Spectral parameters of broadband signal common to digital records 1 & 2

f0_broad = 0.

tau_broad = 2. / Fs # correlation time

G0 = 1.

seed = None

sig = rd.signals.RandomSignal(

Fs=Fs, t0=t0, T=T,

f0=f0_broad, tau=tau_broad, G0=G0,

noise_floor=0., seed=seed)

N = len(sig.x)

t = sig.t()

# Generate two digital records that are identical *except* for

# timebase offset `tau`. Note that `x1[0]` physically occurs at

# time `t[0]`, while `x2[0]` physically occurs at time `t[0] + tau`.

x1 = sig.x.copy()

x2 = rd.signals.sampling.circular_resample(sig.x, Fs, tau)

# Add uncorrelated noise

Gnn = 1e-6 # [Gnn] = [signal]^2 / [Fs]

noise_power = Gnn * (0.5 * Fs)

noise_amplitude = np.sqrt(noise_power)

x1 += (noise_amplitude * np.random.randn(N))

x2 += (noise_amplitude * np.random.randn(N))

# =============================================================================

# =============================================================================

# Estimate trigger offset and compensate:

# ---------------------------------------

# Spectral-estimation parameters

Tens = t[-1] - t[0] # [Tens] = [s]; full record is 1 ensemeble

Nreal_per_ens = 1000 # [Nreal_per_ens] = unitless

gamma2xy_max = 0.95 # [gamma2xy_max] = unitless

# Estimate trigger offset

trig = rd.signals.TriggerOffset(

np.array([x1, x2]),

gamma2xy_max=gamma2xy_max,

Fs=Fs,

Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

print '\ntrue trigger offset: %f' % tau

print 'estimated trigger offset: %f' % trig.tau

# Now, use estimated value to compensate for trigger offset

x2_corrected = rd.signals.sampling.circular_resample(x2, Fs, -trig.tau)

# =============================================================================

# =============================================================================

# Examine cross phase between for uncorrected and corrected records:

# ------------------------------------------------------------------

csd_uncorr = rd.spectra.CrossSpectralDensity(

x1, x2, Fs=Fs, t0=t0,

Tens=Tens, Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

csd_corr = rd.spectra.CrossSpectralDensity(

x1, x2_corrected, Fs=Fs, t0=t0,

Tens=Tens, Nreal_per_ens=Nreal_per_ens)

plt.figure()

plt.axhline(0, c='k', label='expected')

plt.plot(csd_uncorr.f, np.squeeze(csd_uncorr.theta_xy), label='uncorrected')

plt.plot(csd_corr.f, np.squeeze(csd_corr.theta_xy), label='corrected')

plt.xlabel('f [Fs]')

plt.ylabel('cross phase [rad]')

plt.legend(loc='best')

plt.show()

# =============================================================================Note that cross phase computed after compensating for the trigger offset is in agreement with expectations. The large fluctuations in the computed cross phase at high frequencies is attributable to the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at these frequencies; the trigger-offset algorithm is weighted such that points with low SNR minimally contribute to the offset estimate.