In this repository I am collecting (mostly failed) implementations for a general framework to run a numerical simulation with a set of parameters, such that after a simulation with each parameter configuration has been run, the results can be analyzed.

Note: I am in the process of simplifying the code so I might remove everything that does not relate to task scheduling or result collections to make the code easier to understand.

The goals of each implementation were:

- use only one file of code and one definition of parameters as inputs (as opposed to a structured project)

- provide an interface to the code to register a result and/or a plot such that the intermediate steps of the simulations is documented

- give some mechanism for running independent parts in parallel

The terminology I use is roughly (and partly interchangeably):

- Parameters are python variables that create different behaviour of the model. This can be model parameters itself, stimulus parameters or initial conditions.

- usually these parameters are named and reside eg. in a dictionary or json file

- a Project/Experiment is a numerical experiment (the code)

- a Session is an Experiment together with a list of parameters with which the code is to be executed

- so different grid searches over different parameter ranges would be different Sessions of the same Experiment

- a Task or a Job is a single instance of code with the specific parameters that should be used for that code

- Output of a Task is sometimes defined as one single 'thing', but in most cases, a number of variables that recieve values during the execution of the task can be used by following Tasks as input. Also the output can be anything from single numerical values, to large binary files.

Solving even a portion of these subproblems will help to make the workflow better:

- packaging python code and sending to to eg. a worker in a cluster

- a) serializing python code

- b) caring about dependencies and their versions

- scheduling tasks automatically

- a format in which scheduling dependencies can be stored

- a format in which scheduling dependencies can be expressed with ease

- a format for datastorage that is fast to access, but can flexibly store small or large quantities of data (given that the code producing the data knows how big it is going to be and chooses accordingly)

- documenting the workflow, such that afterwards:

- some document can be generated in which it is apparent what happened when

- data can be inspected at a later date and it is unambigouus which code generated the data

It might be necessary to have two representations of the graph: one abstract that generates another explicit graph that can then be stored.

As example I assume there are functions A and B and sets of parameters for each.

Now we want to run A with each possible parameter and then B on the output of A with each possible parameter for that.

Then we want to aggregate results according to which A parameter was used in the first step.

I use a root object that can eg. contain some description about the simulation that is run.

If we think of the computation as pipelines, that can be defined as sets of nodes at each depth, we can eg. express the tasks like that:

root.foreach(a_params).map(A).foreach(b_params).map(B).groupby(a_params).reduce(mean)Or if we use lists to either mean sequential or concurrent execution, we can also define something like this:

[foreach(a_params), [A, foreach(b_params), [B]], reduce(mean)]

# with foreach being a special operator that spawns a new sub-pipeline for each element in the argumentIf two computations should be done on the output, it could eg. be expressed like this:

# explicitly naming nodes

As = description.foreach(a_params).map(A)

Bs = As.foreach(b_params).map(B)

A_results_means = Bs.groupby(a_params).reduce(mean)

A_results_std = Bs.groupby(a_params).reduce(std)

# or anonymously

root.foreach(a_params).map(A).foreach(b_params).map(B).groupby(a_params).split(reduce(mean),reduce(std))

# or in the list notation

[foreach(a_params), [A, foreach(b_params), [B]], split, [reduce(std),reduce(mean)]]

# split being a special operator that duplicates the dataflow and feeds it to each element of the next listReductions can either be tied to the point where a datastreams end after a fork, but that can be hard to express. Similarly, they could be tied to the fork itself and then go along the computation until they recieve suitable input. The list notation uses the end of a forked pipeline as input to a reduction. However, this does not enable access to eg. an intermediate step in the pipeline. Also the order of forks is important for this process. If two lists of parameters are to be explored by forking the processing twice, the order in which the forks occur limits the reductions that can be expressed.

A more flexible way (but maybe less elegant) would be to annotate the path of the computation along each fork and then filter on a flat table of values.

Eg. a groupby call can not only reduce according to the forks made, but any variable that was used to annotate the computation path.

It also remains to be determined if specifying a dependency tree is done via a "magic" or super object at the root or by collecting all the end nodes that are relevant to the user. If only the end nodes are collected and then the dependencies calculated from there, only calculations that are necessary will be computed. Still it might be more comfortable to add nodes onto a common root and execute all paths that leave from there.

Also redundant computations might have to be removed in a separate step. Otherwise some expressions might become very complicated. But intermediate variables could also be a fix for that.

In any case these representations can only be used abstractly. As soon as we want to annotate which computations have been completed, we need another graph with explicit nodes.

In eg. dask notation this might look like this:

{

'a0': (A, a0),

'a1': (A, a1),

'a2': (A, a2),

'a3': (A, a3),

'b0': (B, b0, 'a0'),

'b1': (B, b1, 'a0'),

'b2': (B, b2, 'a0'),

'b3': (B, b3, 'a0'),

# more nodes for b4...b15

'a0_mean': (mean, (map, getter('some variable'), ['b0','b1','b2','b3'])),

'a0_std': (std, (map, getter('some variable'), ['b0','b1','b2','b3']))

# ...

}This mapping of node to dependency can either be written into a json file or stored into a database if the number of dependencies get large.

A similar format could also be used for storing the dependencies of how data was generated.

Note that the actual dependencies of each result can now be collected exhaustively in terms of data and code:

>>> print_dependencies('a0_std')

['a0',A,'b0','b1','b2','b3',lambda l: (std,(map, getter('some variable'), l))]

}Also the parameters of the fork can be propagated, however when reducing, some parameters have conflicting values:

{

'a0': {'a_param': a0},

'a1': {'a_param': a1},

'a2': {'a_param': a2},

'a3': {'a_param': a3},

'b0': {'a_param': a0, 'b_apram': b0},

'b1': {'a_param': a0, 'b_apram': b1},

'b2': {'a_param': a0, 'b_apram': b2},

'b3': {'a_param': a0, 'b_apram': b3},

# more nodes for b4...b15

'a0_mean': {'a_param': a0, 'b_apram': b0, 'b_apram': b1, 'b_apram': b2, 'b_apram': b3},

'a0_std': {'a_param': a0, 'b_apram': b0, 'b_apram': b1, 'b_apram': b2, 'b_apram': b3},

# ...

}Depending on how the reductions are defined these can be removed (eg. when any values clash somewhere) or are just set randomly.

One straight forward way is to store the python code in plain text. There are toolboxes that serialize the actual bytecode, but when this is stored, it is possible that other pyhton versions can not read the data anymore.

There is a nice hack on github on how to import from a specific git commit in a git repository. That might be interesting: olivaq/python-git-import

For my bachelor thesis I solved the problem in the following way:

- a "Project" folder contains a txt description, a 'main.py' file and a folder that contains the "Sessions"

- each Session folder contains a 'jobs' folder for the meta information of the job, a 'job_code' folder and a text file 'parameters.txt'

- Creating a Session: the 'main.py' python file of the Project contained a comment block in which possible parameters are presented

- When a new session is created this block can be edited to give a range of parameters rather than a single value

- in the file, a ´job´ definition is present that looks like a

forloop that allows nested batch jobs (see example)- the bare syntax for a job definition is: 'job "Name of Job":' (the code of the job is then indented)

- to create a batch of jobs (eg for each combination of values from some lists

aandb), the syntax is:job "Name of Job" for value_a in a for the_other_value in b: - a statement 'requires previous' prevents a job to run as long as the previous job is unfinished.

- the bare syntax for a job definition is: 'job "Name of Job":' (the code of the job is then indented)

- to create a batch of jobs (eg for each combination of values from some lists

- so effectively it is a preprocessor for python

- (I can not really remember whether and how this worked, but all my old code looks like this and it worked at one time)

- the downside is, once the jobs

- for each combination of the nested jobs, a new python file is written into the 'job_code' folder

- Running the simulations

- I provided an ncurses gui to create and run a session

- with this gui, the progress and state of each job can be inspected

An example:

job "E1.1. Evaluate Models for Trial Reshuffling" for cell in model_cells for model in range(len(models[0])):

m = models[cell][sorted(models[cell].keys())[model]]

with View(job_path + '_results.html') as view:

b = bootstrap.bootstrap_trials(50,m,data,test_data=[test_data])

stats.addNode(m.name,b)

for (dim, name) in [('EIC','EIC')]:

with view.figure("Cells/tabs/Cell "+str(cell)+"/tabs/"+str(name)):

plot(stats.get(dim))

for k in stats.keys():

with view.figure("Cells/tabs/Cell "+str(cell)+"/tabs/Betas/tabs/"+str(k)):

for b in stats.filter(k).get('beta'):

plot(b)

for b in stats.filter(k).get('boot_betas'):

for bb in b:

plot(bb,'--')

view.render(job_path + '_results.html')

stats.save(path + identifier + E1 + '_' + str(cell) + "_" + str(m.name).replace("/","_") + '_stats.stat')

job "E1.2. Saving Data":

require previous

stats.load_glob(path + identifier + E1 + '_*_Model*_stats.stat')

stats.save(path + identifier + E1 + '_all_models.stat')Additionally, I had created some tools to document the progress of each job with a View and a job reporter class that could generate html with embedded matplotlib plots and a complex tree structure. As I like context managers, these objects can be used heavily as context managers:

# a view contains nodes that are organized by a path string eg. 'A Multiplication Table/table/10/10' will contain 100 in this example

with ni.View('output_file.html') as v:

with v.node('A Multiplication Table/table/') as table:

# /table is a special node name that generates an html table

for i in range(100):

with table.node(str(i)) as row:

for j in range(100):

row.add(str(j),i*j)

with v.figure('A Figure'):

plt.plot(np.sin(np.linspace(0.0,np.pi,100)))

# on exiting the context, the html file is writtenThe job reporter is similar, but generated automatically be the toolbox when a session is updated. It contains the status and return codes/Exceptions of all jobs.

What was good about this solution?

- it worked for the use case I had

- it made it possible to define all code in one file

- it was comfortable to run mutliple jobs in parallel on the same machine

- the gui could be used over ssh

- the job statement for forks and and the require statement were nice ways to create fairly complex dependency graphs

- the view class is still used by me for generating output that needs to be structured

What was not good?

- the preprocessing of python limited the dependencies that can be expressed

- the code that is generated is just dumped into the folder and not really

- there is no way to save annotated data somewhere along the pipeline

For my new project I found the old preprocessing approach to be too limiting. To illustrate the next step, I will first introduce the model I had to run. The model creates psychophysical response functions of visual processes using a retina and a cortex model.

- over a certain range of stimulus parameters I generate stimulus sequences (eg. for each of 8 orientations, a range of spatial frequencies, contrasts etc.)

- for each stimulus, the retinal model (an external program at that time) was executed with one of several configuration files. It generated spike trains as output, as well as some other information

- for each of these simulated spike trains, the cortical model was executed multiple times with different parameters as well. The network creates a large amount of data of which before the simulation it is not clear what is important (eg. firing rate / temporal coding / SNR level or only how well something could be decoded)

- lastly the output of the cortical network has to be analyzed, yet this part should be mostly interactive eg. in an ipython shell

- for each of these simulated spike trains, the cortical model was executed multiple times with different parameters as well. The network creates a large amount of data of which before the simulation it is not clear what is important (eg. firing rate / temporal coding / SNR level or only how well something could be decoded)

- for each stimulus, the retinal model (an external program at that time) was executed with one of several configuration files. It generated spike trains as output, as well as some other information

Because of this, more important than the actual scheduling was the retrieval of data for certain parameters.

I created python classes Experiment, Session and Task that can each serialize themself as json. The most important class to work with was Session, since with one Session object, all the associated data of each Task can be retrieved.

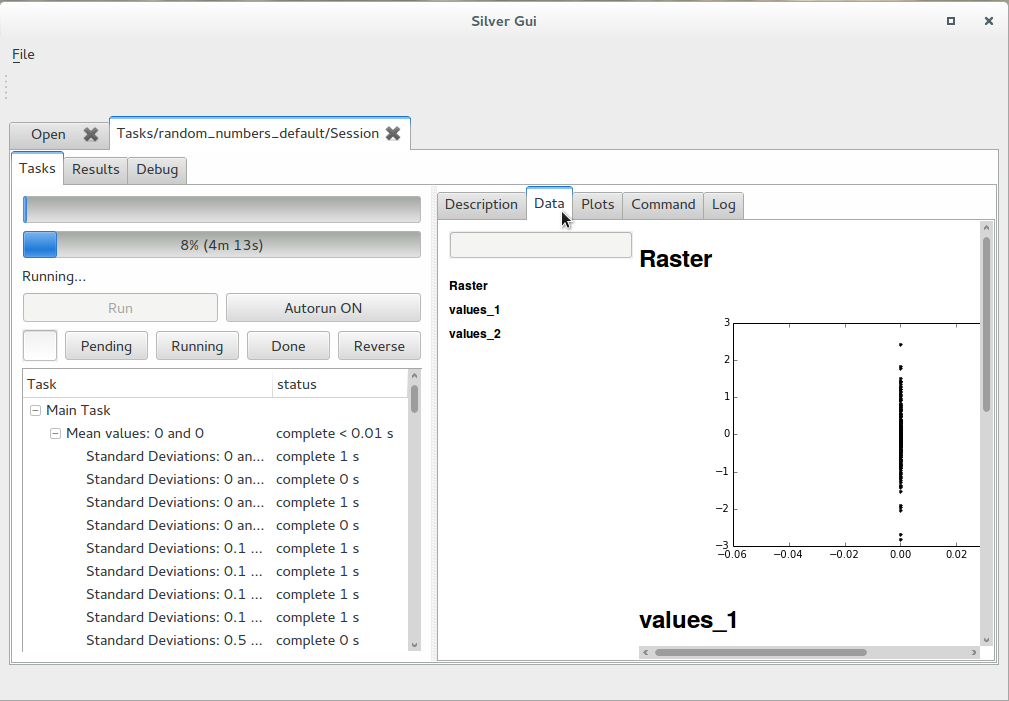

To create a Session, a python file has to be executed (rather than statically analysed) that contains certain functions and dictionaries that can then be accessed by the frontend (a Qt gui). A dictionary of functions gives possibilities of how tasks are created: the function that creates the tasks and dependency structure has to be specified by author of the Experiment. Thus, creating tasks is very flexible, yet tedious (for the author) and hard to follow.

The tasks are also written as text that is then either fed into a python kernel or executed as a system command. A syntax error is unchecked until the task is being run.

Tasks are run each in a separate ipython kernel. Also another ipython kernel is available for processing the results. This kernel has access to a session object (with a fixed name '_silver_session') to query for results while other tasks are running.

A lot of the code that is executed does not live in the experiment files but in the python package that comes with it. When a bug is found, most of the time it occured in the package and is fixed there before the failed tasks are restarted.

The V0.1 folder contains a Tutorial on how to run the code provided.

A python file that after execution leaves the following variables in the namespace:

- description (a string)

- actions: a dictionary of functions that can create a Session for this Experiment. They should return a session object and generate all the necessary Task objects.

- task_context_actions: a dictionary of functions that can be applied to a task (eg. when using the context menu on it)

- possible keywords: 'function' (the function to run, has to accept a Task as its first argument), 'condition' (a function that returns True if this action should be shown for a task), 'kwargs' (a dicitonary of additional parameters that can be changed in a gui before the function is called)

- result_actions: a dictionary with python code that can be run to create result plots interactively

Sessions are serialized into one json file (that also contains all the tasks). This file can become very large and should only be written to by one process. Other than the Tasks, the Session also contains

Tasks are included in the tree of the session json file. As a python Object they also contain a Command object that holds whatever they are supposed to do (execute something or run python code), a status string, start and end timestamps and a dictionary of parameters that are specific for this Task. When the code of the Task wants to get the value of a specific parameter, this parameter will be looked up in this dictionary first, but if it is not found, the parent task is recursively asked. With this, global variables or variables that relate to a portion of the task tree are easy to implement and to change. There is no unnecessary redundancy.

An example task looks like:

{

'name': 'Task to add two numbers',

'status': 'pending',

'parameters': {'a':2, 'b':4},

'cmd': {'scipy': """

the_result = a + b # variables are directly accessible in the namespace

with task.data:

data.add('result',the_result) # task is a provided variable containing the ccorresponding Task object for this task

# the data container is saved and closed once this block ends or fails

"""}

}To save data, each task is provided with a data collector object, which is a save/load wrapper around a dictionary. I had a number of iterations of how to hande the data, but right now they are tar files containing numpy files, strings or pickles (figures can be serialized as strings). For each data key, metadata can be saved as well. Only data that is actually needed is loaded into memory and once data is saved to disk, it is discarded from memory (this behaviour can be controlled with some flags). When data is added to the container, old data is renamed, such that all versions remain in the file. They can be rendered to html automatically (which is used by the qt frontend to show the data).

Even while tasks are still running, the DataCollector files of the successfull tasks can be used to generate partial results. Each task provides a recursive function that fetches named data that was written to its own DataCollector and the DCs of its children. This function has access to the parameters that were provided to the task as well, such that a list of tuples can be returned that can then be filtered by the parameters.

Pros:

- good visualization of results

- scheduler runs reliably picks up automatically where it left off when stopped

- tasks can be altered to be skipped, blocked or repaired

Cons:

- slow! (frontend + no parallelization right now + results take for ever to collect data)

- qt version changes break everything

- especially memory footprint is unreliable

- ipython version changes break everything

- no other frontend (however it is possible to also run tasks from an interactive python shell)

- fixing Exceptions requires rewriting the code by either creating a new session or manually updateing the code property of each job (but also then the results might be a mess: it should be a requirement to document code changes somewhere and which part of the code was run with which versions of which library).

- the created ipython kernels can not be connected to

- sharing memory between ipython kernels (eg. via zmq) could potentially save a lot of memory and serialization/deserialization time. Right now everything is loaded again for each kernel.

- querying for data is tedious/repetitive. There is no simple way to get eg. for each parameter a the mean of some output data. Everything has to be rewritten as loops over and over again. The tree structure of the tasks makes this even uglier.

As an improvement over v0.1, I started implementing zmq communication between a central job distributor and multiple workers that can also be distributed over a network. In the end it should be very similar in behaviour to v0.1, but the frontend, the distributor and the processes running the tasks should be decoupled and run as independent processes rather than threads within the same process. This would then enable multiple frontends to be active at the same time and job runners to keep data loaded if it is needed in the next task, while the distributor should be secured from memory leaks. So far there is not a lot of useable code for that though.

For simpler problems of running parameter combinations and doing something with the results I implemented two classes in the litus package.

These are more an excercise in syntax and usability than an actual solution to a problem.

A litus.PDContainer can hold a dictionary of parameters as well as a dictionary of data and a dictionary of file references.

This class, together with a serializer PDContainerList simplifies managing where tasks save their data to.

Instead of each task having to infer file paths from some parameters, this class provides an easy way to create files are 1) not overwritten by other tasks, 2) can be named the same for each task in the code.

Parameter combinations can be easily generated and a subset of containers can be queried with the find method: for each supplied keyword to the function, the parameter has to match the value.

(this might be extended to django like querying of less than/greater than and evaluation of a supplied function)

Example:

pdl = PDContainerList('a/path/somewhere',name_mode='int') # everything is contained in this folder and containers are named by their id (rather than a combination of parameters)

pdl.generate(a=range(0,10),b=np.logspace(0,1,10))

# (I am tempted to name this class Pudel)

for p in pdl:

p['number'] = randint(10) # will be saved into json, so no large data should be used here!

p.file['large array.npz'] = rand(100,100) # saved as a compressed numpy file.

print pdl.find(a=2) # returns 10 results

print pdl.find(b__lt=4, a__eval=lambda x: x%2==0) # not implemented right now, but easily possible to find all b < 4 and all even a

print np.mean([p.file['large array.npz'] for p in pdl.find(a=2)]) # collects all random matrizes and takes the mean

print 'The filenames: ', [p.file('large array.npz') for p in pdl.find(a=2)]litus.Lists is a context manager for nested lists.

That does not sound very exciting, but it makes it easier to save data into multidimensional arrays, eg. after collecting the results for all parameter combinations.

from litus import Lists

l = Lists()

with l:

for a in range(2):

with l:

for b in range(3):

with l:

for c in range(4):

with l as top_list:

# the context manager gives a reference to a list

for d in range(5):

top_list.append(a+b+c+d)

print l.array() # a 4 dimensional array with shape (2,3,4,5)In combination the parameter ranges of the PDContainerList can be queried with little overhead into a nested list to create aggregates of arbitrary parameter combinations.

My (very buggy) implementations were the result of the current needs, rather than an orchestrated effort. What is still using more time than I would like right now are the following:

- creating a structure for the data I generate, such that it can be locked away and forgotted, but once I wonder about why a result looks like this, I want to inspect everything

- running the same code, no matter whether I am interested in the intermediate results or only one number for each run (as changing code might introduce errors)

- running the same code whether it is locally or remotely

- track the version of every library, package and the exact code that was used to generate a piece of data along with it (the data alone is worthless if I can't find the code)

Distributing numerical tasks on one or many machines + a powerfull dependency solver.

Possibly very specialized, but I have to have a closer look at it. The use of param is interesting.

In the same way Mozaik and Lancet/Lancet for python3 could be the end of all problems. But also maybe not.