authors: Charles Petersen and Jamison Barsotti

this readme is in progress...

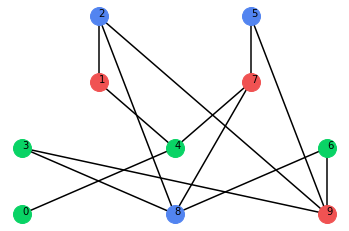

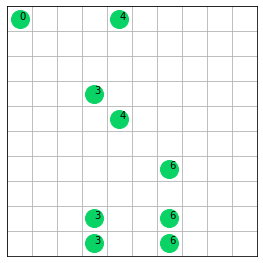

Upset-downset is a novel and complex Tic-Tac-Toe like game created by Tim Hsu. In upset-downset the two players Up and Down alternate turns deleting nodes from graphs like these:

The Up player moves by deleting a blue or green node, together with any nodes connected to it by a path moving strictly upward. (All nodes above the chosen node are removed regardless of their color.) Similarly, the Down player moves by deleting a red or green node, together with any nodes connected to it by a path moving strictly downward. (All nodes below the chosen node are removed regardless of their color.) Eventually one of the players will find they cannot move because there are no longer any nodes of their color. Whoever is first to find themselves in this predicament loses. For an interactive tutorial and to play against a trained Alpha Zero agent checkout this notebook.

We've implemented a version of DeepMind's Alpha Zero, as described in their paper, in order to learn to play Upset-Downset!

For those unfamiliar, Alpha Zero can be very briefly described as a self-play, training, evaluation feedback loop.

In this loop self-play is guided by Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) augmented with move and outcome predictions via a convolutional neural network (CNN). Starting from a game position MCTS samples many branchs of play from the game tree to determine the best course of action. At each iteation of the search, once a previously unvisited node in the tree is encountered, rather than observing the outcome via a random playout the CNN makes an outcome prediction. On the other hand, when a node is revisited, the search combines vist count and outcome statistics gathered during the previous visits with a move prediction from the CNN; focusing in on the most promising avenues of play. Ultimatley the search leads to a superior move choice from the game position than a prediction made by the CNN alone.

In return the self-play generates data in the form of game position, move, outcome triples for each game position encounterd during play. Due to MCTS, the move and outcome here are improved versions of those predicted by the CNN given the game position initially. The CNN is then trained on this self-play data so as to skew predictions during MCTS towards moves that lead to a better outcome when a similar game position is encountered in the future.

The CNN used in self-play is called the alpha agent and the CNN being trained on the self-play data is a copy of the alpha, aptly called the apprentice. After a fixed number of training steps an evaluation is triggered in which the alpha and apprentice agents are pitted against one another in a tournament. If the apprentice prevails (wins more than 55% of the games) then the apprentice becomes the new alpha and the story continues with the new alpha generating the self-play data for training.

We found [blog] to be an excellent source of information when it came time to implememt the CNN in PyTorch. Similarly, A Deep Dive into Monte Carlo Tree Search was a great guide when we needed to implement MCTS in Python.

Upset-Downset is a game played on graphs, and more precisely Directed Acyclic Graphs (or Partially Ordered Sets). In general these graphs are allowed to be arbitrarily large. However, dealing with arbitrarily large graphs is infeasible. We can easily overcome this issue by setting a cap on the size of the games our agent can learn to play.

How did we choose a cap size? Even though a modestly sized game of Upset-Downset is completed in very few moves on average, there are a large number of positions available. For example, there are ~ 1043 Upset-Downset positions amongst games starting with 18 nodes. (This is accounting for the red-blue-green node coloring and the fact that the nodes need to be labelled.) This is much less than the number of positions available on a 19x19 Go board (~ 10170), but still a large space of possible positions when training on a desktop! In order to keep the number of positions tractable and training time feasible we chose to cap our games at 10 nodes or less. In this case there are ~ 1016 postions available. (The code is sufficently general that this number can be increased in the future.)

Since starting positions are variable in Upset-Downset the uniform generation of games is an important exploration step in training our Alpha Zero agent. This is distinct from Go, Chess and many well-known board games where positions in the game progress through play from a stationary starting positon. To insure the agent saw a representative sample of games we needed to generate games in a uniform way. As it turns out, this is a nontrivial question in mathematics about generating partially ordered sets. We started with a naive approach, but soon realized the "random" games we were generating were not at all uniform among the set of posets of size 10.

After a bit of searching, we came across this paper which describes a Markov process for generating random posets uniformly! You can see an example of this in the gif at the top of this document. You can also read more about it in this notebook.

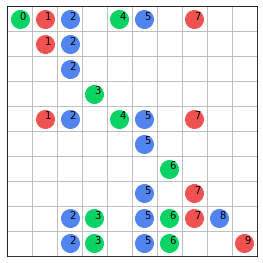

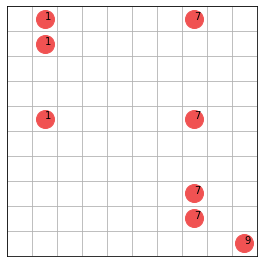

Next we needed to encode Upset-Downset into a format digestable by a CNN. We first represent a game on a board rather than a graph! To do so we use the adjaceny matrix of the transitive closure of the graph underlying the game:

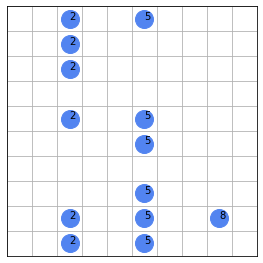

The rules of upset-downset take on a differnt form in the board representation. Can you figure them out? After we have a game in its board representation we decompose the board into 4-channels: the 1st channel holds the blue nodes, the 2nd channel holds the green nodes, the 3rd channel holds the red nodes and the 4th channel holds the player to move (either Up or Down, which we don't depict here):

To get the final representation to feed into the CNN for prediction we convert all nodes on the board to 1 and all empty locations to 0; the 4th-channel is a constant 0 if Down is to move next and a constant 1 if Up is to move next.

**discuss always playing as up...

How can we tell our agent is learning? There are essentially three tests. To explain these we look at the example of our agent that was trained on games of having at most 10 nodes. During this training, 1.5 million games were played over 3 days and ~0 million training steps. The alpha agent updated 6 times. You can find the model parameters here.

The first (and most fun) test is simply to play against the agent and see if it can beat you. As mentioned before, you can do this in this notebook.

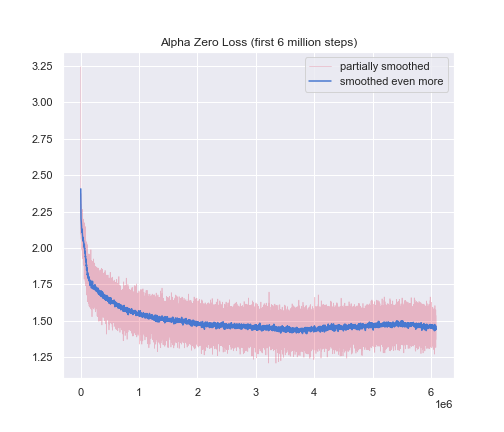

The second (not to mention most ureliable and esoteric) test to determine if the agent is learning is by plotting the loss function over training. Below you can see the agent's loss function over the first 6 million trainig steps. This seems to tell us that the agent is learning on the data we are feeding it; coupled with the fact that it is updating (which implies it's winning games against former agent iterations) is good evidence that the agent is getting better. However, by itself, this metric is a little hard to read. Luckily we have an even better way to know the agent is learning...

Since each upset-downset game will end and one of the players must win, for any particular game of upset-dowsnet the outcome is fixed and must be one of the following: the first player to move can force a win, the second player to move can force a win, the Up player can force a win no matter who moves first, or the Down player can force a win no matter who moves first. By the phrase "player can force a win" we simply mean that on their turn there wlll always be a winning move available, and the player will always choose a winning move.

In our code, each upset-downset game is instantiated as an UpDown object and has at its disposal the outcome() method. So in theory we know the outcome of every game of upset-downset! Alas, this is wishful thinking... the outcome() method is a bare bones, brute force recursive algorithm, so we can't really use it for games that are too big (> 25 nodes or so depending on your system). Though, for games having 10 nodes it is fine.

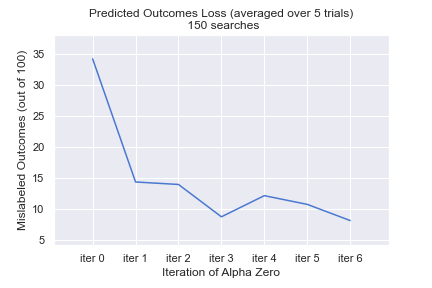

Now, let's flip the perspective and assume we have an agent that will always win if it can. An agent that always makes a winning move if it is available. We should then be able to recover the outcome of any game and hopefully solve the recursivity problem. The issue is then how do we get a perfect agent? Well, this is hard... However, if the agent we train is learning we should be able to use the agent to approximate the outcome of any game. This is precisely what we've done! In fact, for our toy example of games of size 10, we can compare the approximate outcome function to the actual and see if the iterations of our agent are getting better.

The second graph below shows this. We generated a random sample of 100 upset-downset games whose staring position has 10 nodes. We then used each iteration of the agent (including the inital "random" agent) to predict the outcomes of these 100 games. Each agent was allowed 150 MCTS iterations per move. (This is considerably lower than the 600 it was trained on.) We counted the number of outcomes each agent got incorrect (averaged over 5 trials) and plotted this against the agent iteration. We know the agent learned!

class for upset-downset gamesvisualize upset-downset gamesenable upset-downset games to be human playablerepresent upset-downset game as a 4-channel image stack (3D binary tensor)class for nodes in a polynomial upper confidence tree (for Monte Carlo Tree Search).scalable version of the CNN architecture described in the Alpha Zero paper (using PyTorch).agent class to play upset-downset games.markov process for uniform random generation of upset-downset games (generating labelled posets uniformly).fully asynchronous self-play, training, evaluatyion pipeline (using Ray).train an agent on games of 10 nodes or lesswrite an introductory notebook- what's next...

- finish notebooks...

- find memory leak in the async self-play, train, evaluation pipeline...